Bonsai Basics

How to Appreciate Bonsai

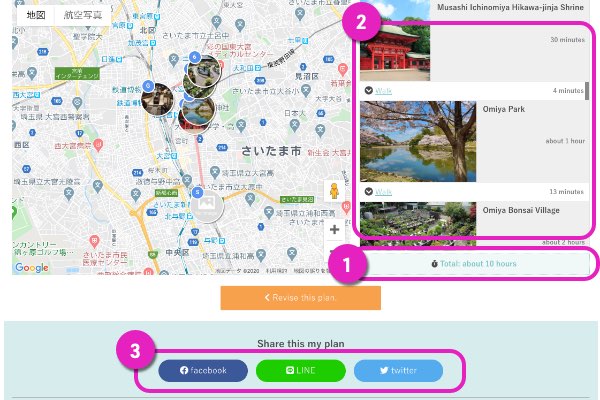

Bonsai are created to condense a vast natural landscape into a compact “living sculpture.” Keeping this in mind, together with the simple steps below, helps the viewer to perceive the artistic expression of each tree.

First, note the bonsai’s “face”: most bonsai are conceived with a clear front and back side. After determining the highlights of the tree he or she is working with, the artisan will pot the plant so that these features face the front, then guide the tree’s growth with the intention that it will be viewed from this aspect. Details that help ascertain the “face” might include branches that spread out like welcoming hands; or a shape recalling a modestly bowed head.

Second, observe that the artisan’s line of sight is oriented to be level with the bonsai’s roots, or the base of its trunk so that the miniaturized tree appears to stand tall. From this vantage point, the viewer can take in not only the figure of the bonsai as a whole, but also individual elements such as the spreading roots and the lower trunk that rises from them; gracefully shaped branches; the hues of foliage; and the solemnity suggested by deadwood on branches and trunks, known respectively as jin and shari.

Types of Bonsai

Trees of many species have the potential to be transformed into the living sculptures that are bonsai. The majority of these species, however, can be categorized into one of two main types: evergreens (shohaku) and shedding trees (zoki). These are then further subdivided into categories defined by both natural characteristics, such as whether the tree bears flowers (called hanamono) or fruit (mimono), and choices made by the artisan when creating a work, such as the direction that branches grow.

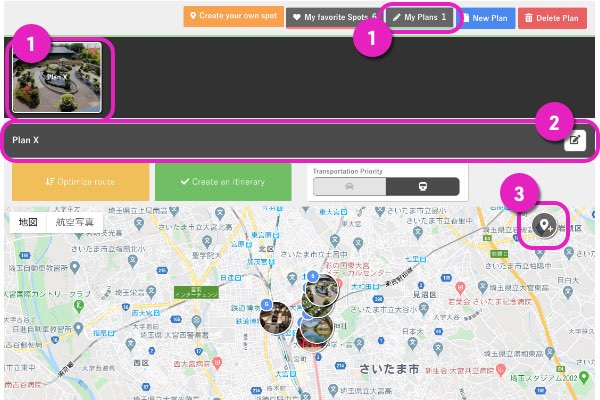

Shohaku bonsai make use of such trees as pines, junipers, and conifers for which the artisan envisions a single image throughout the year. These bonsai, with their deep green foliage and trunks displaying the powerful vitality of the trees, are of a type that have come to popularly symbolize the art in the collective imagination.

Zoki bonsai, on the other hand, use seasonally shedding trees including the Japanese maple, wisteria, and Chinese quince. The artisan creates work that encapsulates nature as it changes through the seasons, the wisteria putting out its elegant sprays of blooms in the spring and the maple’s foliage turning color in autumn.

Shohaku Bonsai, Shimpaku

Zoki Bonsai, Karin (Chinese quince)

Shapes of Bonsai

A number of tree shapes have been formalized as the art of bonsai developed over the centuries. These generally follow patterns observed in nature and, rather than being strictly defined, allow for freedom of the artisan’s creative interpretation. It is not absolutely necessary to conform to any established style.

Chokkan and Moyo-gi

These two upright styles are archetypal bonsai shapes, often seen in bonsai created with trees from the pine family. Chokkan (“formal upright”) features a single straight, upright trunk, while moyo-gi (“informal upright”) is distinguished by a roughly S-shaped upright trunk that tapers as it grows upwards.

Chokkan style Kuromatsu

Moyo-gi style Goyo-matsu

Fukinagashi and Kengai

These two forms convey the notion of a tree persevering against nature’s harsher side. The angled trunk of the fukinagashi (“windswept”) style conjures up a tree battling a strong wind. Similarly, kengai (“cascade”) resembles a tree hanging dramatically down from a sheer cliff. The goyomatsu (Japanese white pine) is among the trees used for these two styles.

Fukinagashi style Goyo-matsu

Kengai style Goyo-matsu

Ne-tsuranari and Yoseue

Ne-tsuranari are bonsai with multiple ground-hugging trunks, often huddled together, that stem from a single root. Tosho (needle juniper) is among the few species that grows into ne-tsuranari. Yoseue refers to trees planted in a tight group to evoke a forest scene.

Ne-tsuranari style Goyo-matsu

Yose-ue style Yezo-matsu

Bonsai Techniques

These common bonsai cultivation techniques, which have been developed over centuries and passed down through generations, can be observed at the Omiya Bonsai Village’s seven nurseries.

Pruning

Pruning, which means removing superfluous or overgrown branches, is key to achieving the desired shape of a bonsai. Imagination contributes to this skill as much as dexterity: since anything cut away can never be restored, the artisan must visualize the result before snipping.

Wiring

Metal wire may be wrapped around branches in order to direct their growth. Success requires that a highly skilled artisan apply this wiring without causing harm, and also that this is done at the most opportune time in the tree’s development.

Creating deadwood: jin and shari

This advanced technique, applied to evergreen shohaku trees, involves creating naked deadwood on branches and trunks (jin and shari, respectively) to mimic the effects of a tree exposed to elements such as wind, snow, and lightning. The bark is stripped off and special jin pliers and engraving tools or sandpaper are used to create the effect. Lime sulfur is applied finally as a preservative to prevent rot.

Defoliating

Seasonally shedding bonsai are sometimes shorn of leaves in early summer, in order to force the tree to grow new, smaller leaves before winter sets in. This can also be done to only select parts of a bonsai to restore balance.

Repotting

All bonsai need periodic repotting, with the frequency depending on the tree species. Overgrown and possibly congested roots are pruned before repotting in fresh soil, which also deals with blocked air circulation inside the pot.

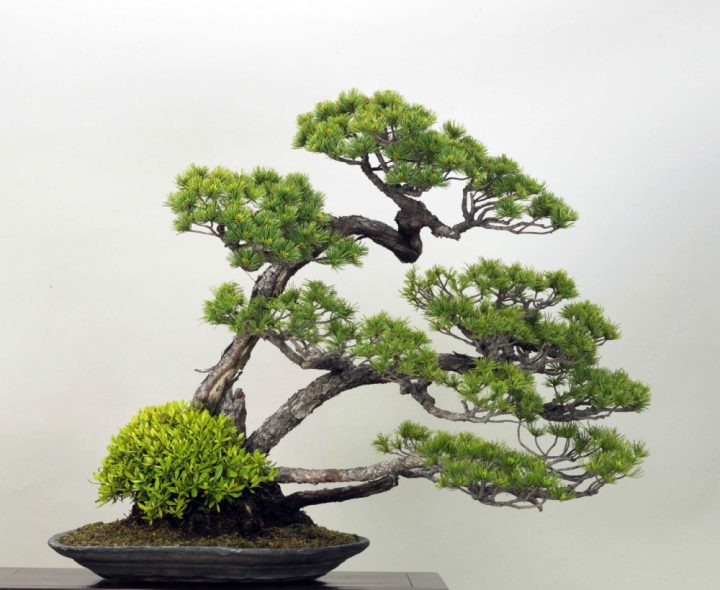

Watering

Watering is the most basic, yet essential, of cultivation practices. Trees generally need watering daily, and a healthy specimen will absorb its water well. The artisan must exercise good judgment in assessing the dryness of soil, since over-watering a weaker tree can accelerate the decay of its roots.

This English-language text was created by Japan Tourism Agency.